Long-running Yorkshire Dales magazine The Dalesman published a series of short reading / article style guides in 1962, and in their ‘The Three Peaks’ guide, there are several pages about the relatively young cyclo cross race.

I managed to get a copy of the vintage magazine (thanks Phil!) and have managed to scan it into real ‘text’ below. Wonderful reading.

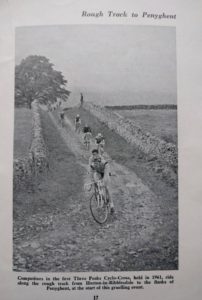

ANY strangers to the Three Peaks area on October 1, 1961, could be forgiven for rubbing their eyes and wondering if they were seeing things. Scrambling up mountain slopes, bicycles across their backs were 35 sinewy cyclists. They were taking part in the first annual Three Peaks Cyclo-Cross, over 25 miles, organised by Bradford Racing Cycling Club and rightly described as the most severe event in the cyclo-cross riders’ calendar. Wheels had come to the peaks in force. Fell walkers and runners could no longer claim exclusive use of this natural obstacle course.

The cyclists have thrown down the gauntlet to the runners, although the challenge has never been accepted officially. The runners’ record is 1 minute 15 seconds under three hours. The cyclists’ record is 3 hours, 21 minutes, 35 seconds. Can the cyclists close the 23-minute gap between the two times ? Divided opinions give added interest to the efforts of both.

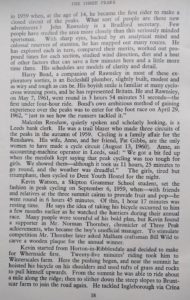

Peak cycling has put many personalities in the news. They include John Rawnsley, winner of the first annual race; Harry Bond, who was baulked by a car in the last few yards but was credited jointly with the victory; Malcolm Renshaw, a pioneer of peak pedalling; and Kevin Watson, a Skipton schoolboy who began it all in 1959 when, at the age of 14, he became the first rider to make a closed circuit of the peaks. What sort of people are these new adventurers? John Rawnsley is a Bradford. secretary. Few people have studied the area more closely than this seriously minded sportsman. With sharp eyes, backed by an analytical mind and colossal reserves of stamina, he has mapped out many routes. He ch in turn, compared their merits, worked out pro-has explored ea posed times for each section, studied wind direction, diet and a host of other factors that can save a few minutes here and a little more time there. His schedules are models of clarity and detail.

Harry Bond, a companion of Rawnsley in most of these exploratory sorties, is an Eccleshill plumber, slightly built, modest and as wiry and tough as can be. His boyish smile is familiar at many cyclo-cross winning posts, and he has represented Britain. He and Rawnsley, on May 7, 1961, went round in 3 hours 54 minutes 51 seconds—the first under four-hour ride. Bond’s own ambitious method of gaining experience over the peaks was to enter for the foot race on April 29, 1962, ” just to see how the runners tackled it.”

Malcolm Renshaw, quietly spoken and scholarly looking, is a Leeds bank clerk. He was a trail blazer who made three circuits of the peaks in the autumn of 1959. Cycling is a family affair for the Renshaws. His wife, Anne, and her friend, Pat Gibbs, are the only women to have made a cycle circuit (August 13, 1960). Anne, an accounting-machine operator in Leeds, said: ” We got a bit fed up when the menfolk kept saying that peak cycling was too tough for girls. We showed them – although it took us 11 hours, 25 minutes to go round, and the weather was dreadful.” The girls, tired but triumphant, then cycled to Dent Youth Hostel for the night.

Kevin Watson,a Skipton Grammar School student, set the fashion in peak cycling on September 6, 1959, when – with friends and relatives at the three summit cairns to provide fruit and pop – he went round in 6 hours 45 minutes. Of this, 1 hour 17 minutes was resting time. He says the idea of taking his bicycle occurred to him a few months earlier as he watched the harriers during their annual race. Many people were scornful of his bold plan, but Kevin found a supporter in Mr. Norman Thornber, chronicler of Three Peak achievements, who became the boy’s unofficial manager. To stimulate competition Mr. Thornber later asked Malham craftsman Bill Wild to carve a wooden plaque for the annual winner.

Kevin started from Horton-in-Ribblesdale and decided to make for Whernside first. Twenty-five minutes’ riding took him to Winterscales farm. Here the pushing began, and near the summit he hoisted his bicycle on his shoulders and used tufts ofgrass and rocks to pull himself upwards. From the summit he was able to ride about a mile along the ridge; then to slither down the steep slopes to Brunt-scar farm to join the road again. He tackled Ingleborough via Crina Bottom. The toughest stretch was near the top, where more carry-ing was necessary. It was a tricky descent through Sulber Nick, the clint-lined gap towards Beecroft Hall where hidden stones in the tufty grass are an added hazard. Back at Horton he ate a snack, and Mr. Thornber warned him not to take risks now that success seemed near. Off he went towards Penyghent, via Horton Scar lane and Hunt Pot. A party of hikers at the summit looked astonished when boy and bicycle appeared. Bouncing down, there were anxious moments when his rear wheel shook loose. Could he finish in his planned time of seven hours? He fixed the wheel and streaked to Horton with 15 minutes to spare.

There he was congratulated by Mr. Thornber and by Mrs. Jackson, wife of the then licensee of the Crown, who offered him a welcome bath and spoke of her own special interest in the peaks. As a girl she had been a keen motor-cyclist, and in the early 1920’s had ridden from Arncliffe to Horton, via Penyghent summit.

The schoolboy’s circuit aroused widespread interest. Bradford Racing Cycling Club revealed that about 10 months previously eight members had cycled over the peaks from Stainforth. But they had stopped for the night at Ingleton, thus failing to complete the tradi-tional circuit. A week after Watson’s success, three members of Leeds C.T.C. Intermediate Section set out. One retired with foot trouble, but Malcolm Renshaw (then 21) and his brother Neil (18) cut halts to a minimum and bnt Watson’s time by about 15 minutes. Renshaw, on September 27, 1959, cut his own time to 4,1 hours. A week later, 12 minutes were clipped off this when Colin Spaven, Harry Bond and Jeff Whittam led the field of six Bradford clubmen who finished out of ten starters. Again Renshaw took up the chal-lenge. On October 11, in his hat-trick of circuits, he went round in 4 hours 15 minutes. Renshaw later joined the Bradford club and pooled his experience with their experts.

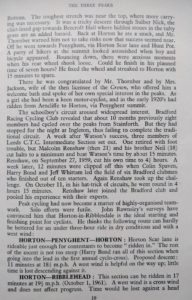

Peak cycling had now become a matter of highly-organised team-work. Solo efforts were futile. John Rawnsley’s surveys have convinced him that Horton-in-Ribblesdale is the ideal starting and finishing point for cyclists. He thinks the following route can hardly be bettered for an under three-hour ride in dry conditions and with a west wind :

- HORTON—PENYGHENT—HORTON :

Horton Scar lane is rideable just enough for contestants to become ” ridden in.” The rest of the ascent is not too steep (Harry Bond ran all of this section when going into the lead in the first annual cyclo-cross). Proposed descent :

11 minutes at 181 m.p.h. A west wind is helpful on the way up; little time is lost descending against it. - HORTON—RIBBLEHEAD

This section can be ridden in 17 minutes at 192 m.p.h. (October 1, 1961). A west wind is a cross wind and does not affect progress. Time would be lost against a head wind. It is an advantage if a group of riders of equal strength can do ” bit and bit.” - WHERNSIDE

A good pace can be maintained under the viaduct to Winterscales farm. From here to the summit the cycle is carried on the shoulder. The last section follows the wall on the right because it provides shelter from a west wind, and the ground forms a natural staircase. The mountain is rideable from the sum-mit along the ridge. The descent to Bruntscar is just rideable. Time is saved if marshals open gates between Bruntscar and Chapel-le-dale. A west wind is no disadvantage on Whernside. - INGLEBOROUGH :

Permission to pass through Southerscales farm was not obtained during Rawnsley’s attempts, so the main road through Chapel-le-dale is taken until a gate on the left is reached at the foot of the hill. Climb the field diagonally and continue up the steep rocks to a plateau. Two routes to choose from now: (1) Follow the wall to the left shoulder of Ingleborough, as the runners do, and strike right to the summit. (2) Make for the strip of grass in direct line to the summit. This is very steep. A west wind is no disadvantage here, but is a head wind on the last part of route 1. - INGLEBOROUGH-SELSIDE-HORTON :

Descend towards Simon Fell. Follow the wall on the right (mostly rideable). Pass to the left of Simon Fell and on to Selside. Progress is much faster in a west wind. The road from Selside to Horton is ideal for a fast finish. Here is a table of achievement and a proposed schedule for a three-hour ride

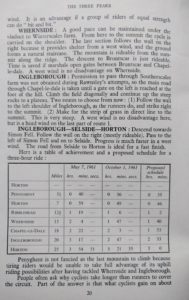

| Miles | May 7, 1961 hrs. : mins. secs. |

October 1, 1961 hrs. : mins. secs. |

Proposed schedule hrs. mins. | |

| HORTON | — | — | — | |

| PENYGHENT | 32 | 0 : 40 | 0 : 36 | 0 : 35 |

| HORTON | 7 | 0 : 59 | 0 : 49 | 0 : 46 |

| RIBBLEHEAD | 124 | 1 : 19 | 1 : 06 | _

1 : 01 |

| WHERNSIDE | 15 | 2 : 04 | 1 : 47 | 1 : 40 |

| CHAPEL-LE-DALE | 18 | 2 : 22 | 2 : 03 | 1 : 53 |

| INGLEBOROUGH | 20 | 3 : 17 | 2 : 47 | 2 : 33 |

| HORTON | 25 | 3 : 54 : 51 | 3 : 21 : 35 | 3 : 00 |

Penyghent is not fancied as the last mountain to climb because tiring riders would be unable to take full advantage of its uphill riding possibilities after having tackled Whernside and Ingleborough. People often ask why cyclists take longer than runners to cover the circuit. Part of the answer is that what cyclists gain on about ten miles of roads and downward slopes, they lose on the rough ground near the summits when machines have to be carried. In the first annual race, Rawnsley estimated that he carried his bicycle on his back for about 1 hour 6 minutes, ran with it for 50 minutes and rode it for 1 hour 25 minutes. To make a three-hour circuit he reckons he will have to cut his carrying-time by over four minutes, his running time by about eight minutes, and his riding time by about nine minutes. Such is the precision of his planning that he works in terms of seconds and fractions of miles per hour as he surveys each section.

Harry Bond, too, has given much thought to these ratios of carrying, running and riding. His curiosity was behind the decision to put aside his bicycle for a week-end and run in the 1962 foot race to see if he could learn a few secrets from the runners. He found the contest far less gruelling than the cycle race, despite the fact that he had begun training only ten days beforehand and had covered no more than four miles at each session. He took special notes of the direct routes taken by the harriers, but was convinced that none would help a cyclist. The steep slopes, he noticed, forced the runners to a walking pace, and without 241b. of bicycle he found the climbing was comparatively easy. Because of lack of training, the punishing trek from Penyghent to Ribblehead was the hardest section. Even so, he came in 18th. His time of 3 hours 22 minutes 48 seconds would have won the race in 1954-5-6 and 7.

The Bradford team have gained much useful information about training and diet. Cramp through excessive sweating is fought off with salt tablets, and sustenance en route is provided with chocolate, bananas and oranges. So exacting is the race that a man can lose up to half a stone. To cut down bicycle weight, riders have experimented with alloy components and plastic saddles. Track machines can be stripped to weigh as little as 181b., but such lightweights would be too risky on the peaks. Pump and spare tyre are considered vital, and these raise the weight to about 23211).

The backroom work for the race is terrific. Organisers Rawnsley and Ron Bowes had to seek access permission from eight or nine farmers. Some farmers were naturally anxious about possible damage. So the club took out third-party insurance for £50,000 to guard against injury, and damage to walls, stiles and gates. Incidentally, there are 15 gates on the course, and marshals have to be picked for open-and-shut duties at every one. Then, as in the foot race, arrangements have to be made with R.A.F. and Army personnel who give valuable service with walkie-talkie links, and stand by with mountain rescue equipment. Police, too, must be consulted. Sixty-eight crack riders from all over the country applied to take art in the first big event, and the sponsors would have liked to accept the lot. But police permission for such a mass assault was not granted. It was heartening that after the event farmers and police spoke highly of its success. There were no complaints. The organisers hope that more riders will be accepted in future.

It is hardly surprising that peak-bagging adventures have proved a delight to satirical writers. One columnist has said he is waiting for someone to complete the circuit on roller skates, or to cross the peaks pushing a pea with his nose. Another suggests a prize for the man who goes round in less than 12 hours holding an orange between chin and chest. High finks in the area have so far stopped short of the ridiculous—except perhaps for a Penyghent invasion by discus-throwing competitors in Roman-style togas. They were part of a stunt to publicise Bradford Students’ Rag Week in April, 1961, and the winner reached the summit in 90 throws. It is on record, too, that a skier streaked from Penyghent summit to Horton in 10 minutes.

Mechanical assaults on the peaks are not confined to two wheels. A Land Rover was hauled round in August, 1951 by men from H.Q. Company of the 12th Battalion the Parachute Regiment. They took 111 hours. The vehicle was bogged down several times. Near Ingleborough summit the men built a track with rocks as inch by inch, with hands raw and blistered, they dragged the vehicle to the top. The true fell walker must abhor this sort of activity. His concern is shared by most lovers of the mountains. But peak-bagging is part of to-day’s passion for record breaking. Few branches of sport are exempt from the stop-watch. Popularity of the Three Peaks area must continue to grow by the very nature of its compactness and its appeal to the imagination. One can only hope that noisy interruptions will be kept to a minimum, and that mechanical invaders will stop short of motor-cycles, go-karts, tanks and peak-hopping helicopters.